Split-second radio-burst from deep space

An international team of astronomers using the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico have discovered a split-second burst of radio waves, providing new evidence of mysterious pulses that appear to come from deep in outer space.

Published July 10 in The Astrophysical Journal, these findings mark the first time that a so-called “fast radio burst” has been detected using an instrument other than the Parkes radio telescope in Australia. While scientists using the Parkes Observatory have recorded a handful of such events, the lack of any similar findings by other facilities led to speculation that the instrument might have been picking up signals originating from sources on or near Earth.

“Our result is important because it eliminates any doubt that these radio bursts are truly of cosmic origin. The radio waves show every sign of having come from far outside our galaxy – a really exciting prospect,” commented Victoria Kaspi, an astrophysics professor at McGill University in Montreal and Principal Investigator for the pulsar-survey project that detected this fast radio burst.

The exact cause of these radio bursts is presenting a mystery for astrophysicists, with possibilities being suggested. These include a range of exotic astrophysical objects, such as evaporating black holes, mergers of neutron stars, or flares from magnetars (a type of neutron star with extremely powerful magnetic fields).

Jason Hessels, co-author and astronomer at ASTRON and the University of Amsterdam, said: “The race is now on to figure out what causes these bursts. If they really originate from outside the Milky Way, that would be extremely exciting.”

Lasting just a few thousandths of a second, fast radio bursts have rarely been detected. However, the latest findings confirm previous estimates that these strange cosmic bursts occur roughly 10,000 times a day over the whole sky. This astonishingly large number is inferred by calculating how much sky was observed, and for how long, in order to make the few detections that have so far been reported.

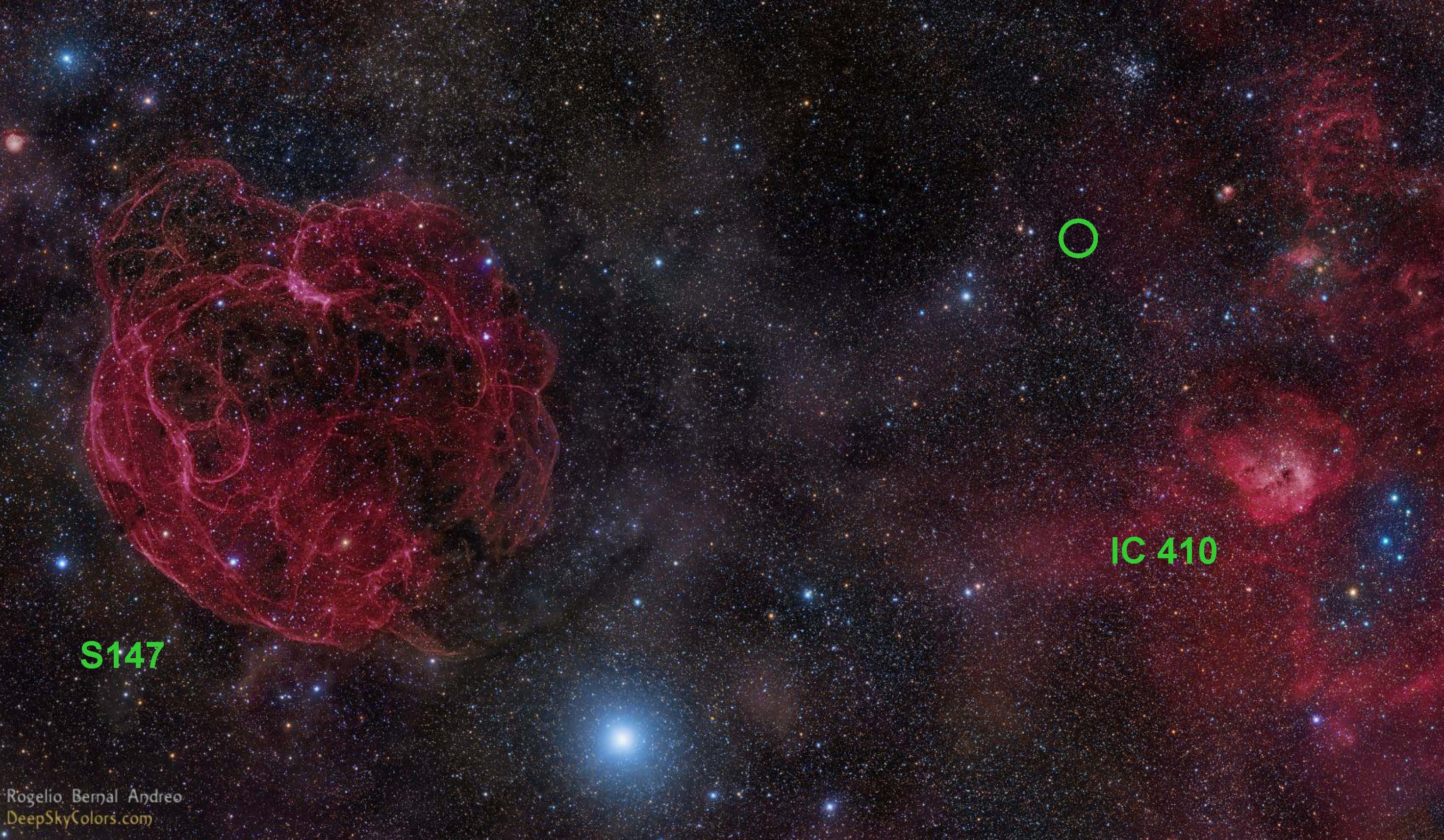

Optical sky image of the area in the constellation Auriga where the fast radio burst FRB 121102 has been detected. The position of the burst, between the old supernova remnant S147 (left) and the star formation region IC 410 (right) is marked with a green circle.

Measuring an effect known as plasma dispersion, researchers believe that the bursts appear to be coming from beyond the Milky Way galaxy. Pulses that travel through the cosmos are distinguished from man-made interference by the effect of interstellar electrons, which cause radio waves to travel more slowly at lower radio frequencies. The burst detected by the Arecibo telescope has three times the maximum dispersion measure that would be expected from a source within the galaxy, the scientists report.

“It’s fantastic that the PALFA survey is discovering not just pulsars, but also other powerful bursts of radio radiation,” added Joeri van Leeuwen, co-author and astronomer at ASTRON and the University of Amsterdam.

Efforts are now under way to use the Low Frequency Array LOFAR and the upgraded Westerbork/Apertif telescope to observe broad swaths of the sky and detect more fast radio bursts. Hessels and Van Leeuwen expect many more discoveries and a better understanding of this mysterious cosmic phenomenon.